One of the most fascinating things about communication is how complicated we can make it. You know what I mean. We’ve all had experiences where we, or someone else, are trying to communicate a very simple concept and doing one or more of the following:

- Using Technical Words vs. Plain English – There are plenty of examples of this in the non-profit sector, but the commercial example really makes the point. This example is from the good people at Convince and Convert, a digital marketing firm.

Here’s a typical explanation of an employee benefit plan:

“Beyond the basic benefit, both individual and spouse buy-up options are available. Please note: an election of voluntary life coverage for a spouse can equal up to half your individual life buy-up, although depending on the desired level of coverages, EOI may be required.”

I have no idea what they’re a talking about. I suppose I could figure it out if I spent a morning with it. But this is all techspeak.

Here is what they’re trying to say:

“The company is going to buy some life insurance for you. If you want, you can buy extra. Whatever extra life insurance you buy for yourself, you can also buy up to half that amount for your spouse. Now, depending on how much additional insurance you’d like, one or both of you may need to answer some questions about your health to see if you qualify for it.”

A lot easier to understand. This way of writing and talking is fostered by the Curse Of Knowledge, where a person unknowingly assumes that the person he/she is communicating to has the background to understand what they are saying or writing.

Jeff and I see this a lot in our mid, major and planned giving work.

- Keeping Everything Factual vs. Using Emotion – We see this all the time. Communication, verbal and written, that is devoid of any emotion. It’s all data and logic… no heart. You and I know that speaking and writing without emotion isn’t real life. Yet so many people in the non-profit sector write about the problem they’re working to solve without any emotion.

- Including Too Much Detail – You’ve been in these conversations or read this copy. This is where the speaker/writer goes all around the barn, to the other side of town, even a visit to a foreign country before getting to the point. Way too much detail and unnecessary information. I’ve often wondered why people do this. One answer was “I give detail so I can be understood.” The problem is that too much detail creates distraction and confusion, so understanding the objective is lost.

- Focusing On Self and The Insiders vs. The Problem and Its Solution – This is a very common problem in non-profit donor communication. Where the language is about us. Our program. Our process. Our great staff. Our facility. The great people we know. Etc. Etc. Now, all of that is good. But donors don’t care about that. They want to solve a societal problem that matches their passions and interests. So you need to adjust your language to be mission-focused and show how the donor can be a partner in the solution.

So, if you find yourself in any of these communication traps, take the following steps to get out:

- Focus on the problem to be solved – Keep remembering that the donor has specific passions and interests that relate to the PROBLEM your organization is working to solve. That should be the focus of your communication.

- Keep it simple – There’s no need to techspeak, use impressive words and concepts, or generally confuse the donor. Keep your communication simple and to the point. Watch out for too much detail.

- Get emotional – Own the fact that life is emotional and that humans are emotional. We like our facts and our data. But facts and data tell. Emotion sells.

- Watch out for the Curse of Knowledge – Don’t assume your listener/reader knows what you’re talking about. Constantly check yourself on this point. More often than not, you’ll likely talk over the head of your audience. We seem to do that despite ourselves.

- Write like you speak – You speak in incomplete sentences, with pauses, sometimes interrupting the flow, abruptly changing the focus of your words to bring clarity, etc. Write like that so that the donor can understand.

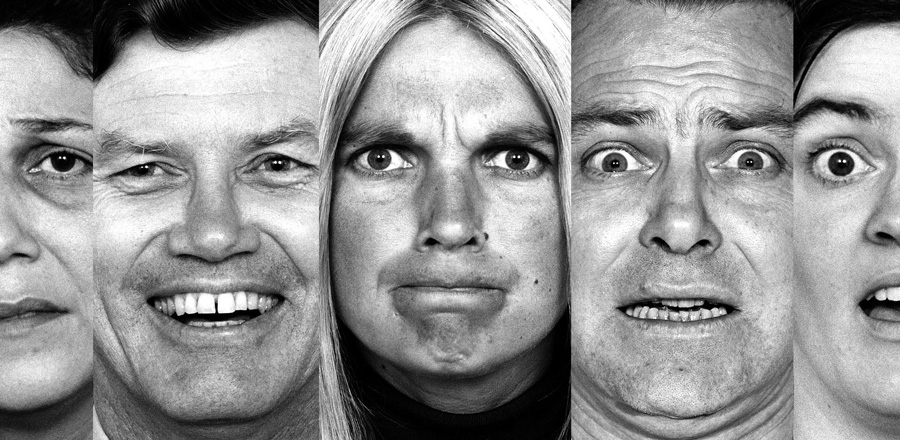

- Watch the body language – If you’re present with the donor, watch their body language to see that you’re communicating effectively. If you’re not present, pay attention to what the donor writes back IF she does, or the tone of the response. Note the reactions. Read the feedback. It will tell you if you’re talking and writing like a human.

If there’s one thing Jeff and I and our team have learned over the years, it’s that people want authentic connections – real conversations. Real means human. Make sure your donor communication delivers that.

Richard

Very good information. Well stated. I would add to the list avoiding acronyms, internal jargon and internal speak.